In Conversation with Stephanie Douet & Roshan Chhabria

/Installation view at India Club, London

British artist Stephanie Douet works with various media, from painting and sculpture to photography and installation. Her life-size two-dimensional and three-dimensional works portray fictional characters influenced by the colours, textiles and perspectives of Mughal paintings, and the dream-like quality of 19th century sepia photography. Equally interested in portraiture, Baroda-based artist Roshan Chhabria employs watercolours to depict the mundane day-to-day activities of the Indian middle class. His works have graced the walls of various galleries and fairs in India, including Gallery Maskara, Latitude 28, Gallery Ark and the India Art Fair.

Coming from diverse backgrounds and different parts of the world, Stephanie and Roshan first connected via Instagram while chatting about the British Raj. This developed into a collaborative series titled Indo-Anglian Conversations, which was exhibited at the India Club in London. We caught up with Stephanie and Roshan to talk about their artistic collaboration, creative process and the way their works have been influenced by one another.

Stephanie, what sparked your curiosity about the British Raj?

Stephanie Douet: When I went to India for the first time, I knew nothing about the British Raj. In the Udaipur City Palace, I came across this gloomy room with old photos of British political agents. The whiskers and buttons had been carefully painted on. I was fascinated and intrigued; who were they and why were they there? I read more on the subject from an Indian perspective in books by Shashi Tharoor, E.M. Forster and William Dalrymple (White Mughals), and I grew increasingly appalled. In the UK, the bad things about the Empire are never discussed; only World War One and World War Two.

I was gripped by the beauty and mystery of the photos in Long Exposure: The Camera at Udaipur 1857 - 1957 and read my copy until it fell apart. I would draw over some of the photos, tearing them out, blowing them up to life-size and painting the princes and the political agents over and over again. The subject is a little tricky; as much as the topic intrigues me, I try to be cautious about cultural appropriation, and focus on my own discoveries through research when it comes to tapping into inspiration

Roshan, your work expresses the dilemmas of coming from a conservative middle-class background versus the liberal environment of an art school. How did you become an artist, and how did your family react?

Roshan Chhabria: Going to art school was not planned. I am from a conservative middle-class Sindhi family of businesspeople. My grandfather came to India from Sindh in Pakistan during partition and started a small shop selling dhotis on the street.

The elders in my family are bound to their old ideologies. But I was young and had more exposure to the world. I wasn’t good at studies – I failed three times. Being influenced and fascinated by modern culture, I wanted to open a shop for ready-made garments during the first year of my BA program. My father disapproved as he felt I needed more experience, but I was impatient, so I started it in secret. I ended up making a loss and, distracted by job tension, I also failed in all my subjects that year.

I did a one-year course in fashion design and got a job at a boutique. There I saw fashion design students drawing on dresses. I didn’t have enough skill to draw like them, so I attended painting classes at Mudra School Of Fine Arts. A lot of people had come there to prepare for the Fine Arts entrance exams at MSU Baroda. Though it was never my intention to do fine arts, I took the exam and got admission.

I hadn’t said anything to my parents until then. On my first day of classes, I told my father and he got really angry with me. He told me he wouldn't give me any more money to pursue fine arts. I worked part-time at a boutique and sometimes, my mother would help me out monetarily. My mother struggled a lot to save money for me. In my second year, I started teaching drawing to children in the Play-Centre, and I worked there until I left for my Masters in Visual Arts.

Tell us about your first conversation on Instagram. How did your working relationship develop?

SD: I came across Roshan's work on Instagram in 2016 when I was looking for an artist to chat with about the British Raj in India. I loved his drawings; they are witty and real. He skilfully translates his own real life experiences into his paintings with a delightful awkwardness that makes them very compelling to look at.

We started chatting, and though I quickly realised that he wasn’t particularly interested in what had gone on between the Indians and the British, we continued our conversation – talking about other aspects of our own work. What we had in common rose above our differences. He is a young man from sunny Baroda and I'm a (ahem!) mature woman from drizzly Norfolk.

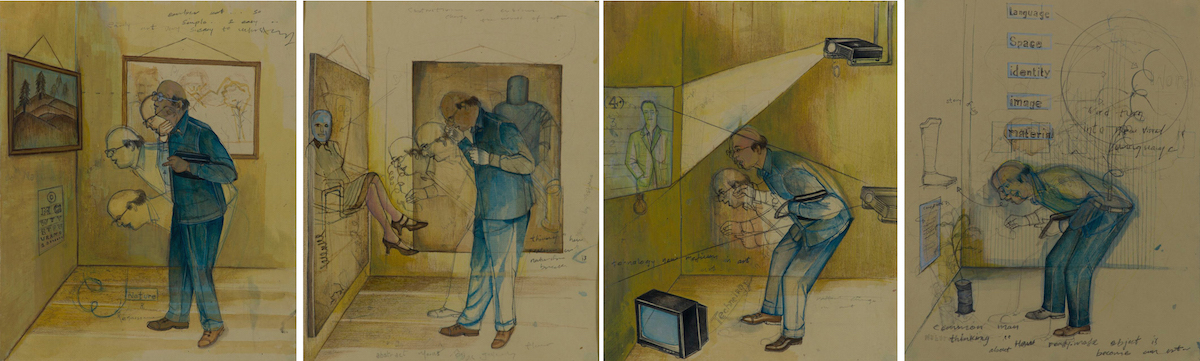

RC: We both like to use similar things in our work: humour, black objects, kinetic drawing and text. I like the forms in Stephanie’s work, and I find it inspires my subconscious. My painting of a woman in a saree is a good example of her influence.

Roshan Chhabria, Weight of a brain, 2013

Young boy sleeping till 11 am, 2018

Roshab Chhabria, Medium changes according to time, 2013

What were your thoughts on Stephanie's interest in the Raj? Did it interest you?

RC: No, I’m not very interested in the Raj. But like Stephanie, I like the old photographs of the British and the black and white photos of rajas. I like her paintings of moustaches on rajas.

SD: Were you taught much about the Raj at school?

RC: Yes, but I was very bad at school, I missed it all. At art school we talked about the art that was produced during the time of the East India Company. British artists did a lot of documentary work on India like Thomas and William Daniell's on-site sketches. In fact, I get a lot of my information about the Raj from you, Stephanie!

Actually, when you first asked me if I would like to talk about the Raj, I thought you meant Company painting, which I really like because it documents Indian festivals, animals and street culture. The style inspires my work to an extent, so it was very interesting for me to talk to an English artist about it. I am also quite friendly, and I like talking to people even without any specific reason.

How does your collaborative process work, in a practical sense?

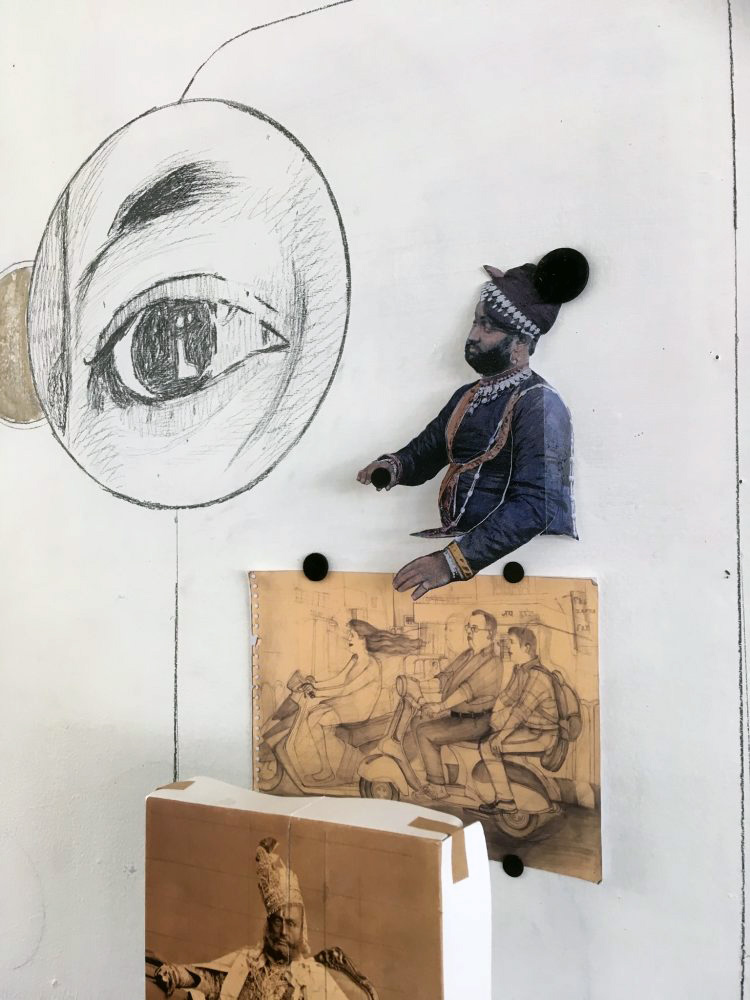

SD: We really wanted to work together in some way and we came up with an easily managed idea where we would send each other drawings to be printed out and drawn on – photos of objects, suggestions for artistic actions – and put the results up on the studio wall. This method worked immediately! We wanted to give a lively impression of what our chats feel like, so we created a framework with the typical rounded-edge text boxes, emojis and favicons to reference our relationship through Instagram. I copied Roshan’s font style into the Instagram ‘boxes’. Within this framework we put anything that came into our heads – collages, sketches, blown-up painted-over photos, even my gritty studio shoes painted black!

In September 2017, we had our first exhibition together at the famous India Club in London. It's a wonderful old hotel in the centre of London – much loved by its regulars, and unchanged since its opening in the 1950s when it was started as a place for Indians and Britishers to meet, so it was absolutely perfect for us! We couldn't draw on the walls or nail up, so we hit on the idea of photographing the work in our respective studios and making two giant photographic prints. This improvisatory way of working is entirely new to both of us, and we both find it exhilarating – which is why we really need to do it in the same place rather than in two different continents with a 5-hour time-lag.

Stephanie's Studio, Norfolk

Stephanie's Studio, Norfolk

Installation view at India Club, London

Stephanie's Studio, Norfolk

Have you ever met in person?

SD: We have indeed! At India Art fair 2018, when I came over to meet Roshan and a curator called Kanika Anand who was interested in our project. Unfortunately, we had very little time as Roshan was installing his work, and our plan to go to Baroda together came unstuck when he got an irresistible exhibition offer. It was delightful to meet him and some of his artist friends.

What are you talking about currently?

SD: One of the things that amazes me about our chats is that by chance I have found a very astute, observant and truthful critic in Roshan. We tend to critique each other’s work, for example, saying what we think works, what doesn't and why, pointing out any connections to other artists' work or ideas, sharing photos of someone else's painting that's exciting us. Some of our energy goes into looking for galleries in India and England that might host a residency for us.

How would you install an exhibition in a gallery? Would your work then become site-specific? Would it be for sale?

SD: We are ready to go with this one! First, there is the idea of a painting performance, where we occupy a space and have a supply of photos, objects, and drawings that we put up. We would like the public to join in with this conversation, sending us Instagram messages that we can write on the walls, or bringing along things we can use in the performance – maybe their own photos or objects. Another thought we have is that we take beautiful photos of our work on the studio walls, and produce them as posters, which could be for sale. At our exhibition at the India Club we had various prints and original work for sale, which we see as another way of extending our conversations out into the world.

Edited by Richa Gupta, founder of Inky Genius.

Installation view at India Club, London